In honour of this weekend’s women’s World Cup final, I thought it would be interesting to do a post looking at how the highest level of women’s football in England, the Women’s Super League, compares with the Premier League in terms of levels of competitive inequality. I’ve calculated the same four measurements used in analysis of the top men’s European leagues (fully outlined and explained in this post), then presented a side-by-side comparison of each measure (for every season it is possible to calculate) since the WSL started in 2011.

A few points to have in mind:

- Over the period in question, the WSL’s format has gradually evolved, expanding from an eight team league to a league of twelve teams. You are, therefore, dealing with a shorter season than the Premier League.

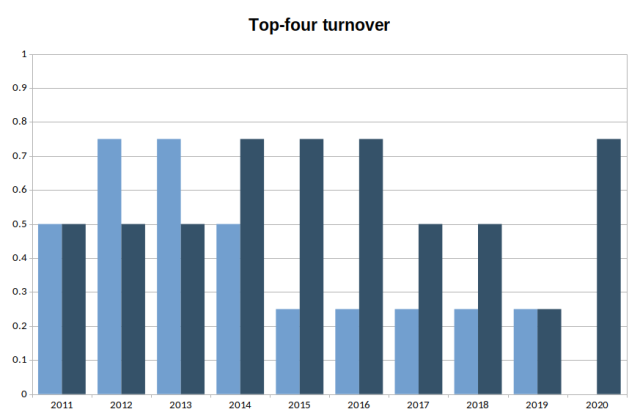

- Because of the smaller league size for the WSL, I haven’t gone beyond the top four when looking at the turnover measure.

- The figures listed here for the WSL for 2017 were for a particularly short interim ‘Spring Series’ competition of just eight games, used to bridge a gap caused by a shift in the overall schedule of the playing season from summer to winter.

Results

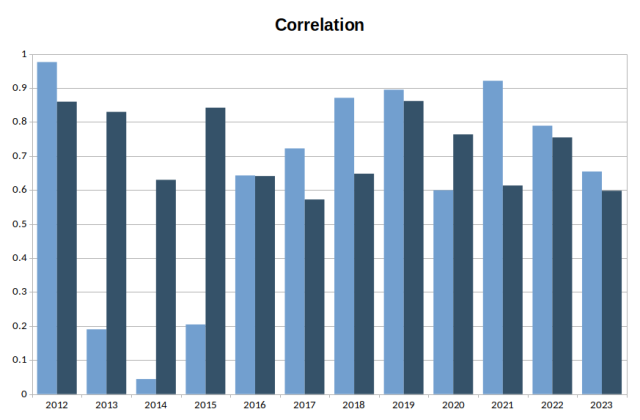

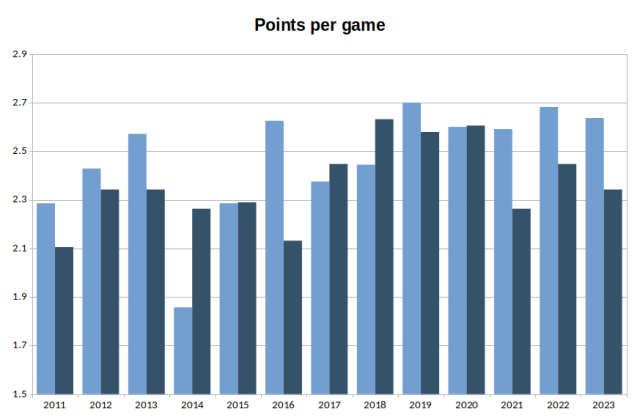

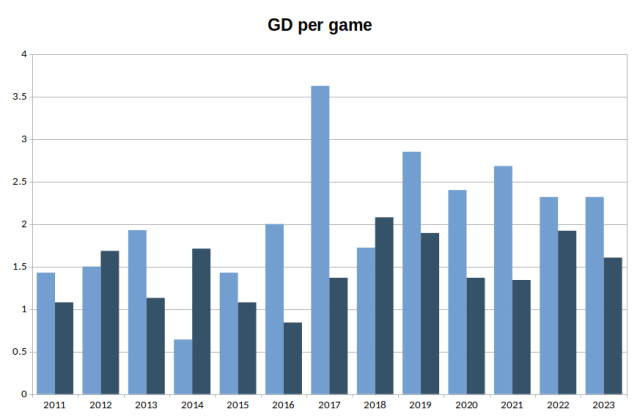

For each graph, WSL results are shaded light blue and those for the Premier League are shaded darker.

There are some things that can be clearly see from the results:

- After a few early years of flux, the WSL has settled into a very similar pattern to that of the men’s game, with high levels of stability (high correlation in finishing positions from season to season, low levels of turnover in top positions) and high levels of dominance by the winners (in terms of points per game and goal difference per game).

- In fact, the figures point to unequal competition having become more of a factor in the functioning of the women’s game than the men’s.

- In particular, the top positions of the WSL have been dominated by three teams: Chelsea, Man City and Arsenal. In fact, 2023 marked the first occasion since 2014 that one of these teams finished out of the top three — Man City were fourth, as a result of Man Utd finishing second.

- The WSL champions consistently achieve better goal difference than those of the Premier League, built upon large numbers of easy wins. The pinnacle of this was the 2017 Spring Series mentioned above: in the eight games they played, champions Chelsea recorded two 7-0 wins, one 6-0 win and two 4-0 wins.

What can we learn from this?

Unequal access to resources is just as much of an issue for the state of competition within women’s football in England as it is in the men’s game, even if the financial standing of the two leagues are very different. Absurd money is not sloshing around the WSL in the manner it does in the Premier League. In fact, women’s teams remain largely dependent upon their affiliated men’s clubs for much of their funding, which means affiliation with a wealthy Premier League men’s side is becoming almost a prerequisite for any sort of success. Indeed, in the 2022-23 season, the only WSL side not backed by a Premier League team was Reading, who finished bottom and were relegated, after which financial constraints have led them to switch from fully professional to part-time status.

What this also helps to show is that the level of effective competition within a league is not a function of the absolute levels of resources it has access to, but rather as a result of how resources are spread within the clubs in the league. The Premier League has not got less competitive in the past couple of decades because of the increased wealth of its clubs, but rather because of the inequality in resources that has created various levels of hierarchy between those at the top and those lower down. Meanwhile, WSL teams have experienced varying levels of success because some clubs have been quicker and more lavish in the investment they have dedicated to their women’s teams.

The good news for the WSL is that its problems seem easier to remedy, as the ongoing development of the women’s game (aided by, at the very least, a World Cup final appearance) is likely to make more Premier League clubs come to see the benefits of investing in a women’s team, meaning that more teams may be given the resources to challenge in future. The scale of the disparities in the men’s game, meanwhile, feel like far more of a daunting obstacle toward the delivery of a healthily competitive Premier League.