In a comparison, who’s better: Manchester City of 2022-23 or Manchester United of 1998-99?

In the red corner: coming from an era of dominance in the 1990s to claim their fifth Premier League title in seven years (their 12th champion’s crown overall), their tenth FA Cup victory and their second European Cup. A vibrant and tenacious side featuring the graduates of the famed Class of 92 (Giggs, Scholes, Beckham, the Nevilles, Butt), alongside Roy Keane, Dwight Yorke, Jaap Stam, Peter Schmeichel and Andy Cole, all driven by perhaps the best manager of all time, Alex Ferguson.

In the blue corner: capping their own era of recent dominance with a fifth league title in six years (a ninth overall), lifting the FA Cup for a seventh time and taking a first European Cup victory. Tactically meticulous and finely honed under Pep Guardiola, with technical virtuosity throughout the team in the likes of Kevin De Bruyne, Rodri, Bernardo Silva and Ilkay Gundogan, fronted by the bulldozing goalscoring prowess of Erling Haaland.

So how do you decide..?

One approach you could take would be to consider each side’s best eleven, player-by-player, and through some arbitrarily subjective rating system try to uncover which was superior. That’s the angle taken in this piece in the Telegraph, which declares the United eleven to be better by a quarter of a point (although, if you read the opening blurb, you find these exact line-ups started precisely five games between them across the two seasons). Well, I guess it drives engagement, eh…

But, what can a comparison of the two teams tell us about what it means to be a dominant team in their respective eras? Rather than simply seeing it as a contest, can we use a comparison to better understand the state of English football then and now?

Let’s start with some comparisons of the respective performance of each team in their treble-winning season.

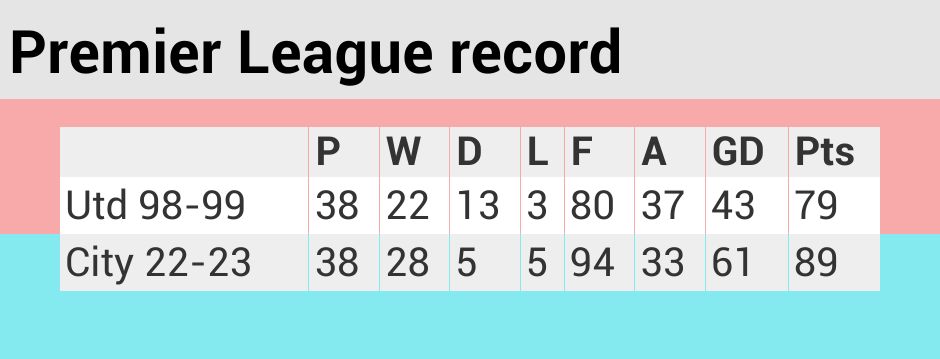

Premier League

Here, there’s a clear edge to City’s performance: they won more games, achieved a higher points tally, scored more goals and were stingier defensively. United, though, proved harder to beat, only losing three games all season.

There are, also, similarities with the way both seasons played out. Neither team won from the front: both were behind the top spot at Christmas, but hit rich spells of form as the season progressed – United’s last defeat was on the 19th December, City won 12 straight games from February until the title was wrapped-up. Both ultimately triumphed over Arsenal to take their title: City won theirs with three games to spare, while United had to record a final day victory at Tottenham to see off the Gunners.

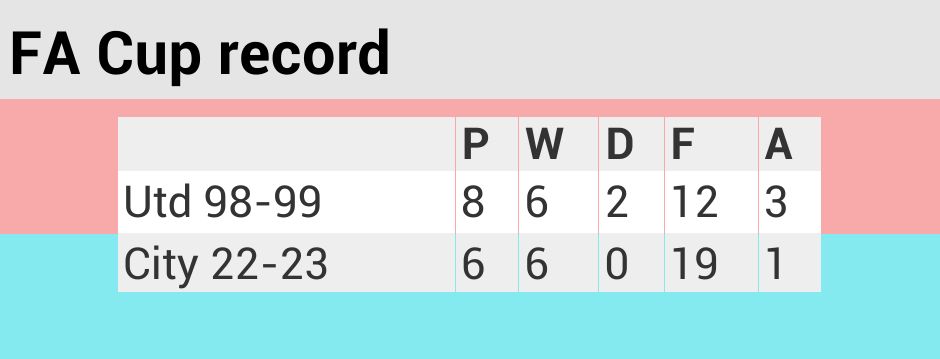

FA Cup

Of course, as victors of a knockout trophy, here neither lost a game. City again, though, show greater dominance in respect to goals scored and conceded over their cup run, while United required replays to overcome Chelsea in the quarter-final and Arsenal in the semi-final (the momentous game in which Keane was sent off, Schmeichel saved a Bergkamp penalty in injury-time, before being settled by Ryan Giggs’s memorable weaving dart through the Arsenal backline and ecstatic hairy-chested, shirt-waving celebration in extra-time).

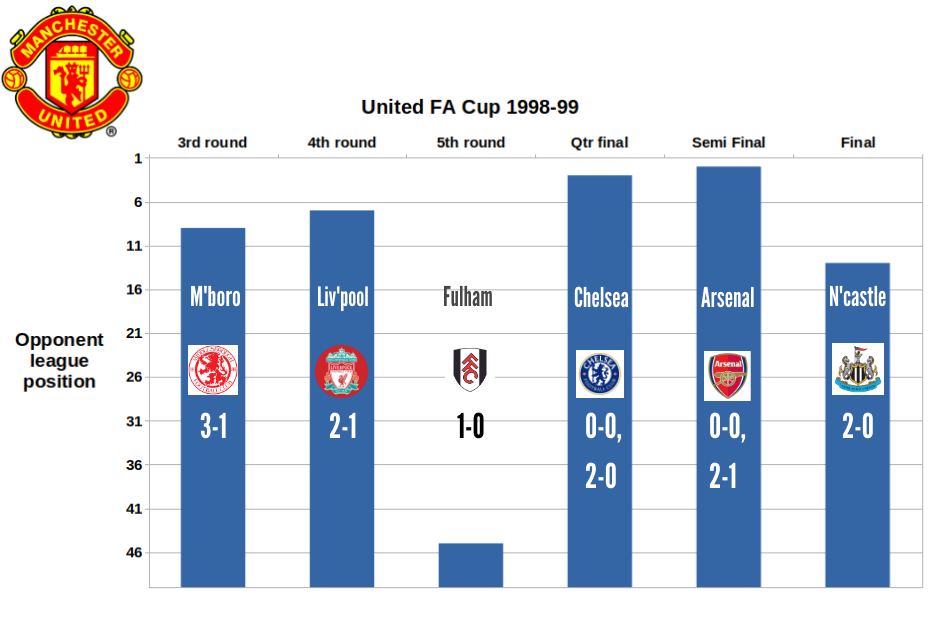

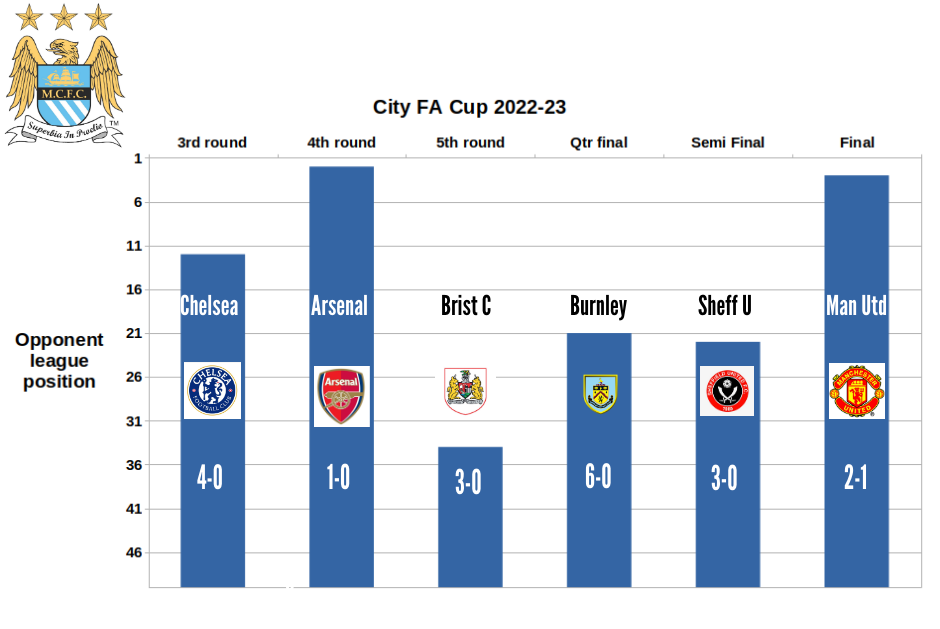

Although, with any cup run, who you are drawn against can make a big difference, so it is worth looking at the respective cup runs, to see where across the league each of their respective opponents finished.

Here, United probably had the harder path, with four of their six opponents being top half finishers in the Premier League. Interestingly, both City and United had to overcome the teams who finished 2nd and 3rd in the Premier League on their way to the trophy.

Another feature common to both cup runs was facing teams who were having great success in lower divisions: City faced the teams who finished 1st and 2nd in last year’s Championship table, dispatching both of them comfortably; United’s sole lower division challenger was Fulham, at that point on their way to a 101 point season in the third tier under Kevin Keegan, as Mohamed Al-Fayed’s millions began to push them towards the Premier League.

One respect in which both City and United were both lucky was in being given more home than away fixtures: United were drawn at home all the way to the neutrally hosted semi-final (although they still needed to win away once, in a quarter-final replay at Chelsea); City’s only away tie was against Bristol City – the lowliest side they faced.

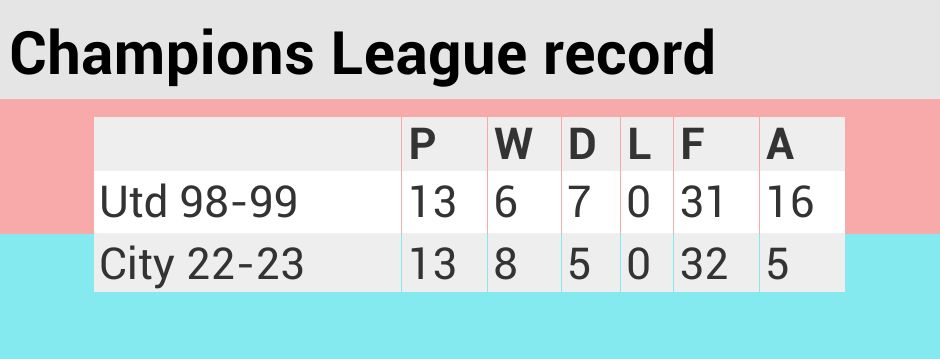

Champions League

Both teams went through all stages of the competition unbeaten, with City shading things on their overall record. While both sides played thirteen matches in their campaign, for United, this was only due to their need to play a qualifying tie prior to the group stage, beating ŁKS Łódź 2-0 over two legs. The expanded format of the competition required City instead to play four two-leg knockout ties after the group stage, compared to just three for United.

United were a swashbuckling side across the 1998-99 European campaign, frequently involved in high scoring games. Highlights included two 3-3 draws with Barcelona and a 6-2 win over Brøndby in Copenhagen in the group stage, alongside a thrilling 3-2 win over Juventus in Turin (when Roy Keane put in a career-capping performance to drag them back from an early 2-0 deficit) that took them to the final.

City’s Champions League victory was more of a pulverising experience – they simply ground opponents into the dust. This was particularly the case across the knockout phase as RB Leipzig, Bayern Munich then Real Madrid were dispatched 8-1, 4-1 then 5-1 on aggregate.

There is possibly a case that changes in the format of the competition made City’s path through the groups stages easier than that faced by United, as in 1998-99 only two clubs per country gained entry to the tournament. So, while both sides faced groups drawn from exactly the same three leagues (Germany, Spain and Denmark) United’s group contained the eventual German and Spanish league champions in Bayern and Barcelona, whereas City’s opponents ended up finishing second in the Bundesliga (Borussia Dortmund) and twelfth in La Liga (Sevilla).

Even if this was true, though, the ease with which City batted aside the German title winners and the previous Champions League winners in the knockout phase points to a level of dominance over the competition that was never apparent in United’s rollercoaster path to the trophy.

Digging deeper

The above confirms the on-first-sight observations that most fans would have considering the two seasons side-by-side: there was a sense of crushing inevitability about City’s performance last season that wasn’t present in United’s treble of 1998-99. United’s season was thrilling to follow precisely because there were so many high-stakes situations that could have gone in different directions yet, somehow ended up falling the way of Ferguson’s team. With City, instead the impression was of an awesome power that might sometimes briefly be contained, yet was never really at risk of being overcome.

But, does this tell us more about the teams themselves, or about the wider state of competition within the sport?

Context: domestic football

Firstly, we can look at domestic performance in perspective by examining two of the measures of inequality used in the C0mpetitive Inequality Project.

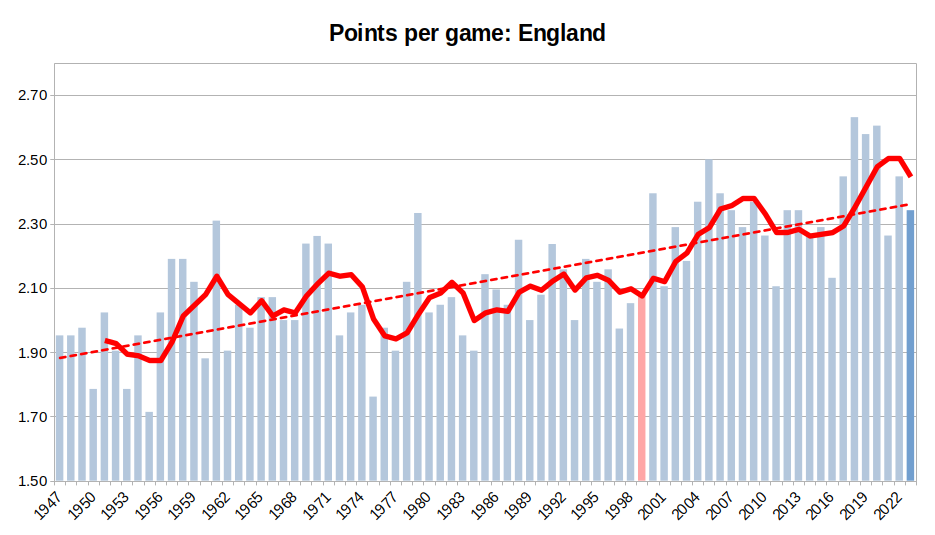

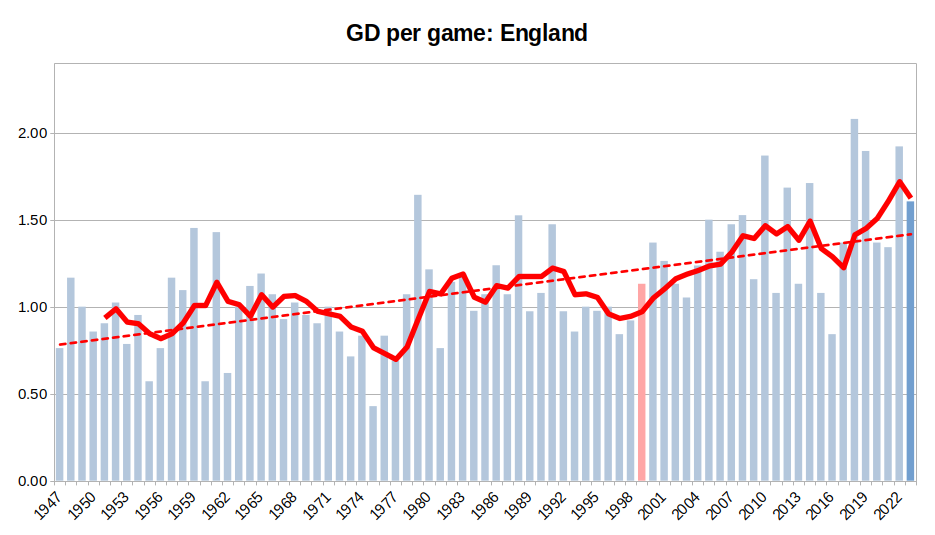

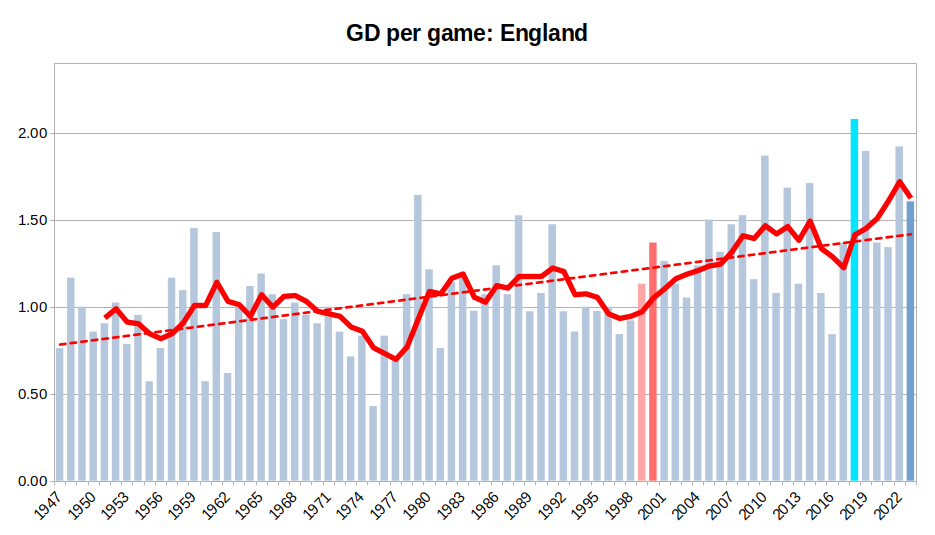

Here first are the charts for points per game and average goal difference per game, with the relevant treble-winning seasons highlighted.

(Bars here represent the individual measure (average points won, average goal difference) per game by the team that finished champions that season. The red line is a five-year rolling average to pick up on trends in the medium term. The dotted line is an overall trendline representing the overall direction of travel for this measure across the results. United’s 1998-99 performance and City’s 2022-23 performance are highlighted. See this post for further discussion of these measurements.)

In terms of points per game, both treble seasons were slightly ‘down years’: performance was lower than many of the surrounding seasons for both teams, while both fell short of the overall dotted trend-line. I guess this shouldn’t be too great a surprise – maintaining a challenge on multiple fronts may require that sometimes league performance dips, due to things like tiredness or squad rotation. (City also had to contend with the disruption caused by a mid-season World Cup.) Goal difference per game figures show this to a slightly lesser extent: United are closer to the trend, while City sit above it, although still below many other recent seasons.

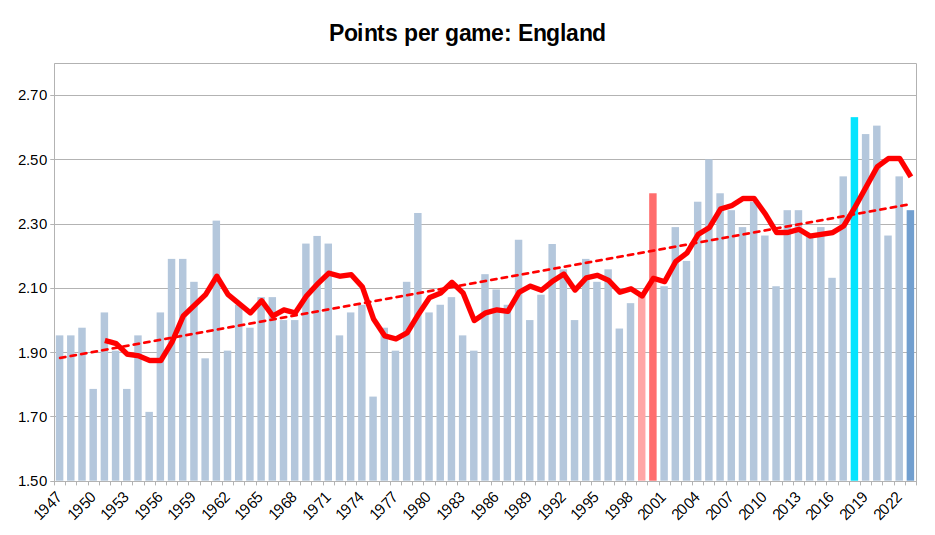

If it is the case that league performance suffers across a season where multiple trophies are won, what would things look like if, rather than comparing the treble winning seasons themselves, we instead look at the peak performance each team achieved (or has achieved so far, in City’s case).

As shown in the darker red here, United followed up their treble with their most impressive league performance under Ferguson, hitting 91 points in 1999-2000. This is above City’s points haul last season and was higher than anything that had come before. However, it has been surpassed on multiple occasions since, including the 2017-18 season (highlighted in sky blue) in which Guardiola’s City reached 100 points to set the current record performance.

Given the overall trend towards higher performance by clubs at the top of the table, it becomes harder to assess teams from different eras, but one thing we can say is that both of these seasons clearly stand out above the dotted trend line (City probably shading things in terms of how far above trend they were), showing that each team at its best was something special.

As with the treble-winning seasons, the goal difference per game measure gives a greater edge to City. Even in United’s best league season (by points won), their goal difference only just sits above the trend, while City’s best season is well clear. This gives us a really clear indication of the level of controlled domination that this current City team is able to exhibit: their ability to hold and use possession in a way that allows them to break opponents down without exposing themselves defensively. It also attests to the growing gap between City and the majority of the Premier League in terms of resources available to build a team that most will struggle to live with.

Context: European football

While the difference between the Premier League of 1999 and that of 2023 is great, the differences in European competition – and particularly in English football’s standing vis-a-vis continental football – are probably much bigger. City’s Champions League win this year was the third by an English club in the last five renewals; seven of the last twelve finalists in the competition have been English teams. This is all a far cry from the late 1990s, when English football was still struggling to reassert its importance following its late 1980s exile from European competition as punishment for the involvement of Liverpool fans in the Heysel Stadium disaster.

There had been some success in the European Cup Winners’ Cup: United themselves claiming the trophy in the first year back after the ban in 1990-91, followed by Arsenal in 1993-94 and Chelsea in 1997-98. But the performance of English teams in Europe’s premier club competition remained short of the swaggering dominance they had exercised in the pre-ban era. After the return, none of the first three English participants – Arsenal, then Leeds, then Manchester United – made it into the tournament’s group stage (although, in the nascent experimentation with a group format, the group phase was then at a relatively later point than it would come to occupy as the format became established).

United’s first post-ban appearance ended in memorable, although ignominious, fashion when they were unable to overcome Galatasaray over two legs. The first leg had seen the Turks come back from an early 2-0 deficit to take a 3-2 lead, before a late Cantona goal left things level leading into the second leg. On arrival in Istanbul, though, it became clear that United were not facing an easy task. The players were met by a mob of fans at the airport, who loudly chanted “No way home” and carried signs bearing intimidatory slogans, such as the infamous “Wellcome to the hell” (sic). Many travelling fans found themselves detained by police on spurious grounds, preventing them from attending the match. The game itself was played in a raucous atmosphere, lit by the constant glow of fan flares, with the home team taking great delight in using all of the tricks of the trade (although the term ‘shithousery’ is relatively recent, the behaviour it captures has a long pedigree) to knock their more illustrious opponents off their game. The game, which ended 0-0 to secure the Turkish side’s progression on away goals, frequently descended into rancour, ending with altercations between Turkish riot police and United’s players and staff. When asked about the experience afterwards, Ferguson pointedly quipped “I’ll no’ be going back” (although he did, when United again drew Galatasaray in the following year’s competition).

The failure of the English champions, who were then already running away with the following year’s title, to overcome a side from a country who England’s national team had twice beaten 8-0 in the previous decade seemed emblematic of the struggles of the English game to hold its place against rival leagues. The fact the tie came just weeks after a 2-0 defeat for England against the Netherlands had all but confirmed that Graham Taylor’s side would not appear at the 1994 World Cup compounded the sense of England’s status as being on the periphery of the European game.

There was, then, something of a feeling of having a point to prove in United’s run to the trophy in 1999. Yes, English football had clearly moved out of its early-1990s doldrums, with fine performance by the national team at Euro 96 and the continued development of the Premier League starting to draw great players in from overseas, but triumph at the top club level in Europe was still missing. So, even for English fans who were typically fervent ABUs (Anyone But United), the fact that they could pull off results like the victory in Turin over a side containing the likes of Zinedine Zidane, Edgar Davids and Didier Deschamps contained a thrill as a vindication of English football’s resurgence.

Compare that with the current moment, when clubs throughout the Premier League have purchasing power that rivals or surpasses clubs anywhere else on the continent, making England the place where the world’s top players want to be. City, even before their success, were regarded by most as the pre-eminent European club side and were clear betting favourites at the start of last season’s Champions League. There was, then, less of a sense that City were grappling with a challenge that could possibly still be beyond them, less of a feeling after the final that they had overcome the odds to be there. Football in Europe is very different now and English clubs are situated in a position where success is expected, rather than being a dream.

TLDR: who’s better?

It’s quite clear throughout everything I’ve looked at that this City team has the edge in terms of performance: they dominate games more thoroughly, meaning their success always felt more assured and the gap between them and their closest competitors, both domestically and in Europe, felt wider.

But if you were to ask me which season I would rather relive as a fan of one of these teams, or even as a neutral onlooker? United. Every time, no question. The degree of unpredictability that characterised their treble season gave the games a visceral charge that often feels missing from much of the top level of contemporary football. To be clear, this is less a comment on the two teams than the game itself. The underlying financial tectonic plates have shifted over the past 25 years, in a way that enables Premier League clubs to attract eyeballs and funding from across the globe, opening up the potential for previously unimaginable levels of dominance. Don’t get me wrong, this City side is superb and their success is far from inevitable: those involved in the football operations at the club have not simply relied on exercising financial muscle, but have strategically developed an intelligent set-up, capped by superlative coaching. They play attractive football in a devastatingly effective way that can be a pleasure to watch. But ultimately, no matter how finely crafted the details of its construction, there will always be some missing element of true sporting joy when you remind yourself that what you are watching is the world’s most well-resourced football club smash aside all-comers without ever really looking like they have to extend themselves.